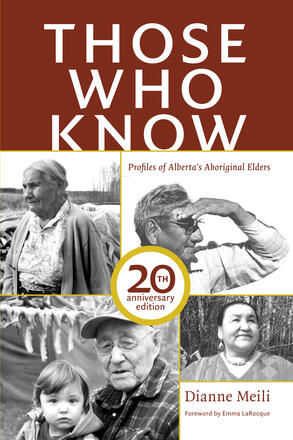

Those Who Know

Profiles of Alberta's Aboriginal Elders (20th Anniversary Edition)

Description

The elders in Those Who Know have devoted their lives to preserving the wisdom and spirituality of their ancestors. Despite insult and oppression, they have maintained sometimes forbidden practices for the betterment of not just their people, but all humankind. First published in 1991, Dianne Meili’s book remains an essential portrait of men and women who have lived on the trapline, in the army, in a camp on the move, in jail, in residential schools, and on the reserve, all the while counselling, praying, fasting, healing, and helping to birth further generations. In this 20th anniversary edition of Those Who Know, Meili supplements her original text with new profiles and interviews that further the collective story of these elders as they guide us to a necessary future, one that values Mother Earth and the importance of community above all else.