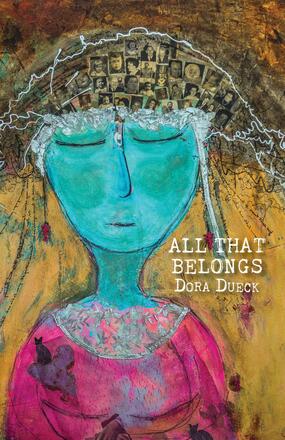

All That Belongs

La description

Catherine, an archivist, has spent decades committed to conserving the pasts of others, only to find her own resurfacing on the eve of her retirement. Carefully, she mines the failing memories of her aging mother and in the process, discovers darker family secrets. All That Belongs is an elegant examination of our own ephemeral histories, the consequences of religious fanaticism, and the startling familial ties—and shame—that bind us.