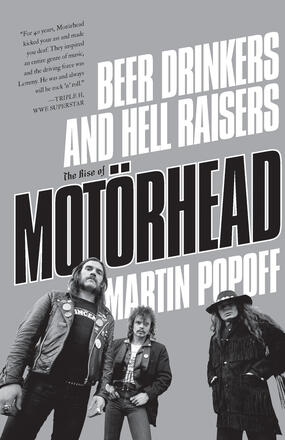

Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers

The Rise of Motörhead

Catégories: Music

Éditeur: ECW Press

Afficher les détails de l'édition

Extrait

CHAPTER 1: “Hang on, what drugs were we doing that day?”

Born on the dole, born in the land of misfit rockers and always—always—born to lose, Motörhead was also born of a burn, its rank figurehead, Lemmy Kilmister, on fire to avenge his firing from the ranks of Hawkwind through the assemblage of a sonic force that would deafen all naysayers. Its name would be Motörhead, and the classic lineup this book celebrates—Fast Eddie Clarke, Phil “Philthy Animal” Taylor and lynchpin Lemmy his bad self—would grind up seven years’ worth of posers and pretenders. Motörhead would create a contrast against the industry, one that will live forever as the potent realization of punk ethics applied to original rock ’n’ roll and a bastard format called heavy metal, a genre nomenclature curiously dismissed by all three soldiers as mirage, but ultimately so much a part of their legacy, their home and hearth, their final resting place against a pop culture that rarely cared.

One mustn’t forget or diminish the accomplishments of lineups after the classic trio—most notably the band as it existed for the near quarter-century with Phil Campbell and Mikkey Dee—but one also mustn’t forget that the classic lineup was not the original, and that the original . . . well, this is one of those happenstances where technically the original, or most salient, “lineup” just might consist of an army of one, namely Lemmy Kilmister.

Born on Christmas Eve in 1945 (and dead three days after Christmas 70 years later) in Stoke-on-Trent, England, Ian Fraser Kilmister, an only child, seemed destined for a life of independence and defiance. His father, an ex–Royal Air Force chaplain, left his mother when Lemmy was but three months old, and his mother, after nine years of single motherhood, took up with a footballer and washing machine factory worker who arrived with a couple of kids of his own, neither of whom Lemmy cooperated with. Stridently resentful of his father, conversely of his mother, Lemmy says, “She was a good mum. She was fair enough. She had a lot of good ideas. ”

Later, living on a farm in north Wales, Lemmy says he “used to breed horses when I was younger, before I got into rock ’n’ roll. ” He also was an enthusiastic reader, having been encouraged by his English teacher, and he worked the carnival when it was in town. But he soon discovered girls and rock ’n’ roll, at its birth in the ’50s. The only English kid among seven hundred Welsh children, Lemmy needed an edge against the inherent territorial resentment he suffered there. Always strategizing, Lemmy took his mother’s Hawaiian guitar to school to impress the girls. “It worked like a charm too,” recalled Kilmister to Classic Rock Revisited. “I saw this other kid with a guitar at school. He was immediately surrounded by chicks and I thought, ‘Oh, I see. ’ Luckily, my mother had one laying around the house, so I grabbed it and took it to school. I couldn’t play it. Eventually, they expected me to play so I had to learn a couple of chords. It turned out all right. ”

Lemmy recalls how, as a young boy, he used to have to go to the “electrical appliance” store and order records, after which they would arrive in three weeks’ time. Early favorites included Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Tommy Steele, Eddie Cochran, Elvis and Little Richard, who he always called the greatest rock ’n’ roll singer of all time.

But it was the Beatles that really lit the fire—Lemmy, all of 16, hitchhiked to Liverpool to see what the fuss was about and watched them live at the Cavern Club before they even had a record out. Our hero soon would play guitar in bands like the Sundowners, the Rainmakers, the Motown Sect and the mildly legendary Rocking Vickers (sometimes spelled Rockin’ and sometimes spelled Vicars), who managed to tour Europe and distinguish themselves as the first western band ever to play Yugoslavia.

“The Beatles had an influence on everybody,” Lemmy told Goldmine magazine. He admired the Beatles as hard men from Liverpool against the Stones, suburban Londoners in his estimation. “You have to realize what an incredible explosion the Beatles were. They were the first band to not have a lead singer in the band. They were the first band to write their own songs in Britain because we always just covered American songs before that. Everybody was singing at the same time and the harmonies were great. Daily papers in England used to have an entire page of the paper dedicated to what the Beatles had done the day before. When George died, the guards at Buckingham Palace played a medley of George’s songs during the changing of the guard; that sort of thing never happens. ”

Lemmy says that his Rocking Vickers were as famed and respected in Northern England, north of Birmingham, as the Who and the Kinks were down in London, but that the other guys in the band seemed to content themselves with playing a predictable circuit, while he had grander plans. But even though the money was good, at £200 a week each, they couldn’t get a foothold in London themselves. And so, dispensing with the Rocking Vickers—which Lemmy ultimately describes as less of a garage band, more of a show band—he left the band house in Manchester empty-handed. “When I left the Vickers, the guitar stayed,” noted Lemmy to Classic Rock Revisited. “It was a band guitar. When people left that band then the instruments stayed and I think that really made a lot of sense. If you need a guitar player but he hasn’t got a guitar then you have one for him to use. When he leaves, you have one for the next guy so you don’t have to run around. ” Traveling light not for the last time in his life, Lemmy found his way to London where his mind was about to get expanded through his apocryphal internship as a Jimi Hendrix roadie, living for a brief spell with bassist Noel Redding and road manager Neville Chesters.

“Lemmy has been my friend since 1963,” explains Chesters, who also worked with both the Who and Cream. “The story goes, and I can tell you, we have a different one on how the story goes but it ends up the same. I actually took Lemmy to London. He came to see us at the Odeon in Liverpool. He wanted to go to London; he asked me if I could give him a ride to London and I said yes. He slept on the floor of my room and then the next day I took him down to London via his house, which was inconvenient. He grabbed a few things. Gone to London, I said, ‘Where do you want to go?’ And he said, ‘Well I don’t really have anywhere; I was wondering if I could stay with you?’ His band then had been the Rocking Vickers, and I’d known him since then. So I happened to have a basement hovel that had three beds. One of them was given over to Noel when he was supposed to share the rent. And I had a spare bed, so Lemmy was in there. And then the next day it was . . . he couldn’t get a job at all. He couldn’t get anything, so I got him a job as my assistant to roadie for Jimi. And that was, at the time, his big claim to fame. In fact for years it was his claim to fame. It was a story that used to come out in many of his radio and TV interviews. But we have a different way of describing how he got to London. ”

“I mean, I used to say he did his work,” says Chesters, unwittingly helping to establish Lemmy’s reputation as unsuitable for any gainful employment other than the haphazard helming of his own shambolic show. “I did an interview for a documentary, and they say to him, ‘Didn’t you roadie with Hendrix at one time?’ And he goes, ‘Speak to Neville about that. ’ So I get a phone call. So, ‘Yes, he came in supposedly to help me’ and they said, ‘Did he work? Did he do anything?’ And I said, ‘Yeah. ’ And they said, ‘Are you sure?’ And I said, ‘Well what do you mean?’ ‘Because most people said he just hung out with the band. ’ And I said, ‘Actually, come to think of it, yeah, that’s what he did. ’”

“It was very confusing because we were tripping all the time,” reminisced Lemmy in October 2006. “[Hendrix] came over to England from America and there was this guy named Owsley Stanley the Third. He was one of those guys who had a laboratory and he gave Hendrix about ten thousand tabs of acid. It was even legal back then. Hendrix put it in his suitcase and gave it out to the crew—there were only two of us. We had the best acid in the world in 1967 and most of 1968. After a while it doesn’t affect your work because you learn to function. I drove the van from London to Bletchley, which is about 150 miles, on acid with a pair of those strobe sunglasses on. They had the vision of a fly, where you would see eight times around. I drove the van with those on for 150 miles on acid, and we got there. ”

Lemmy’s also been known to say that he would score drugs for Mitch Mitchell as well, but when obtaining acid for Jimi, he said his pay came in the three tabs of ten that he would have to take on the spot, while Jimi took seven.

But working for a genius must have been a trip of its own. “Oh yeah, everybody knew it as soon as he came to England,” continued Lemmy. “When he came to the States, you had Monterey and everybody knew about it. It was like that in England. He played one show and everyone knew. It went around like a wildfire. Pete Townshend came out of a club where Hendrix was playing and Eric Clapton was going in. Eric asked Pete, ‘What is he like?’ and Pete replied, ‘We are in a lot of trouble. ’ We used to get Clapton sitting in a chair behind the stack with his ear pressed up against it trying to figure out what he was doing. But I was just hired part time while he was in England. When he went abroad, I was not invited. I was living at Noel Redding’s house and he needed an extra pair of hands. I have been really lucky. I have been in a few of the right places at the right time. My street credibility is incredible. I saw the Beatles at the Cavern, too. It ends up that I was on hallowed ground but it was actually a filthy hole. ”

“Lemmy was there about three months maximum,” laughs Chesters. “Somewhere between two and three months. After that I really only saw him intermittently. After the Hendrix thing, we always had the same women, one way or another. Sometimes I got there before he did and got one over, but only infrequently. In the early days he wasn’t the most outstanding musician I’d seen, but he did pull himself together and managed to be . . . he’s almost an icon, Lemmy, and it’s funny. It’s not necessarily because of his music. There was a period in the mid- or the late ’70s where he was known to hang out with debutantes in London. Now you know Lemmy, you know what he looks like, we all know the features. And none of us could understand why there was constantly, almost weekly, photographs of him in the leading London newspapers hanging out with debutantes. But that’s what he did. And he became an icon. ”

“I lived with him for some time,” muses Hawkwind saxophonist Nik Turner, answering Lemmy’s drug question. “I thought Lemmy was a lovely guy, actually. We got on very well. He was a bit difficult to live with in some ways, because he would be sort of on a different time scale to other people in the band. He went his own way very much. I mean, the band were leaning towards a psychedelic sort of influence, really, and Lemmy wasn’t particularly into psychedelics. He was more into speed, you might say. ”

Plus, he wasn’t much of a hippie. More like a biker, says Dave Brock. “Yeah, we used to know a lot of the Hells Angels in the early days and all that. But Lemmy was always more so buddies with them. I mean Motörhead had more of a problem with them than we did. Lemmy used to always put down on his guest list, ‘Hells Angels England. ’ And sometimes you wouldn’t know who the fuck was turning up there. You’d go to his dressing room, and all the food and drink would be gone and you’d walk in, ‘What the fuck?! We don’t know anybody here. ’ A bit problematic sometimes, you know. But we still do the odd bikers thing. We get along well with them actually. I mean, a lot of them are our age now. Their festivals are always well organized, well together. You very rarely get any trouble. ”

With respect to Lemmy’s burgeoning recording career, following up his three singles with the Rocking Vickers, in 1969 Lemmy appeared on his first full-length record, Escalator, by Malaysian percussionist Sam Gopal. Lemmy is credited as Ian Willis, as he had been considering changing his last name to that of his stepfather, George Willis. Already long known informally as Lemmy, for years it was assumed the nickname came from young Ian’s frequent attempts to borrow money, as in “Lemme a fiver. ” However, Lemmy later confessed that he made up the story and had been paying for it ever since.

“It was very convoluted, because we had no songs,” recalls Lemmy, when asked about those Sam Gopal days. “And then I stayed up all night on methamphetamine and wrote all the songs on the fucking album in one night. I was playing guitar then. But we never really could play live shows too well back then because they didn’t have contact mics for the tablas and things, which are very odd to amplify, because they rely on boom inside to get the sound; you can’t really record that. I mean you couldn’t microphone that; you couldn’t then anyway. That was 1968. ”

Lemmy’s next gig, after a brief situation with Simon King as Opal Butterfly, was to provide a breeding ground for Lemmy’s nasty sound, as it rumbled from both his bass and his face.

“After Hendrix, I became a dope dealer for a while and that was a natural apprenticeship for Hawkwind,” laughs Lem. “The guy that played the audio generator in Hawkwind ran out of money and went back to the band. He took me with him because he wanted one of his mates in the band. I had never played bass in my life. The idiot that was there before me left his bass there. It was like he said, ‘Please steal my gig’ so I stole his gig. So me being a bass player was an accident. I went to get a job as a guitar player with Hawkwind, and they decided they weren’t going to have another guitar player. The guy doing rhythm was going to do lead, so they said, ‘Who plays bass?’ And Dik Mik said, ‘He does. ’ Bastard; I’d never even picked one up in my life. And I get up on stage with the fucking thing, because the bass player left his guitar in the gear truck. And Nik Turner was very helpful. He came over and said, ‘Make some noises in E. This song is called ‘You Shouldn’t Do That. ’ And walked away from me. ”

The “audio generator” Lemmy refers to is in fact Dik Mik, and it is said that a mutual fondness for amphetamines cemented Lemmy’s entry into the ranks of the notorious space rockers, through the recommendation of Dik Mik. Ironically, Lemmy’s behavior on speed would also be the reason he’d be thumped from the band later on.

“You’ve got to remember, Lemmy was a guitarist to start with,” notes Hawkwind guitarist and leader Dave Brock, spiritual twin to the original, pre-Motörhead Lemmy. “I mean, what happened was when Dik Mik brought Lemmy along, he didn’t have a bass. We had to go and buy him a second-hand bass. And of course Lemmy’s bass playing is very similar to guitar playing, in a sense, by playing block chords and stuff like that. So it was a different technique. Lemmy’s fantastic, obviously, now, but you have to think that at the time, the way he played, it was just different. So consequently, that’s why me and him used to play really well together, because I used to play similar lines to Lemmy. So that’s why we were able to play together very well. And now when I do a solo album, my bass playing is a bit like Lemmy’s. I play chords on the bass quite often. It’s a style of playing, really. Instead of picking it and playing note by note, quite often . . . it’s hard to explain without playing the bass. But when you’re playing, it’s quite easy, and Lemmy and I used to be able to do that together. ”

“I don’t use distortion,” clarifies Lem. “I don’t use any pedals. No effects, just plug it straight into the amp. Just a basic Marshall, but it’s turned up very loud, and I hit the guitar very hard. That helps, too. But you’ve got to know how to hit it very hard. A lot of people hit it very hard and it don’t happen. Yeah, I’m doing the old-school version, no mechanics for me. Actually I don’t play bass. I play rhythm guitar and a bit of cockamamie lead guitar on a bass—that’s what I do. It’s a unique style but it’s not one that people have copied, if you’ve noticed, so I don’t think it’s that popular, but it works for me. I always hated it when you get a band playing that was really good, and then the riff drops out because the guitar player has to do a solo, and it sounds wimpy as shit with just the bass player behind him. So I always swore I’d never let that happen. ”

Nik Turner drills down further to posit a source for the churning bass sound Lemmy would make famous. “The idea came from the fact that the previous bass player had been Dave Anderson, and Dave Anderson had a Rickenbacker. And Lemmy was a friend of Dik Mik’s, and he turned up at a rehearsal, and he said, ‘Oh, we need a bass player,’ and Lemmy said, ‘Well, I don’t play bass. I play guitar. ’ He’d previously been a road manager for Jimi Hendrix. And we said, ‘Well, you know, there’s a bass here,’ which was Dave Anderson’s bass. And we gave the bass to Lemmy to play in that situation at that time. I’m not saying we gave him the bass. We gave him the bass to play. And then I think that’s where he started, really. Because he was an advocate of the Rickenbacker bass from then on, and he quickly gave it a great popularity, really. But Dave Anderson had played with Amon Duul II and I think he played the Rickenbacker then too. And so Lemmy had the Rickenbacker, but he had a guitar technique, and he played the Rickenbacker bass like a guitar—chords and stuff like that, rather than just notes. So he created his own sort of musical genre, really, with what he had at hand, and the situation he was in. ”

Below proper chords there are bar (or barre) chords and then double stops, which generally refers to two strings being played at once but normally on a bowed instrument. Lemmy would go on to use mostly double stops, switching from fourths to fifths, plus single notes, as well as his turgid and toppy bass sound: lacking in low-end warmth and high on distortion through mid-range and high-end frequencies. His chosen weapon was a Rickenbacker 4001 bass which naturally lacks in low end, even more so when played through a stack and with acceptance of distortion and volume. This general philosophy when it comes to bass puts Lemmy in a club with the likes of Rush’s Geddy Lee and Chris Squire from Yes. The difference is that those two guys want their individual notes, their playing, to be heard whereas Lemmy just wanted to be heard.

“The bass and treble are all the way off and the mid-range is all the way up,” Lemmy told Jeb Wright of Classic Rock Revisited. “I came up with that by just fucking with the sound. I like that sound; it is kind of brutal but that is what we were looking for. I had a Rickenbacker with a Thunderbird pickup on it back in the old days. It was a horrible monster but it wore out eventually. I love the shape of Rickenbackers. I buy guitars for how they look. You can always fuck with the sound once you have them. You always had to change the pickups on the old Rickenbackers because they were crap. Now they have really good pickups. I have a signature bass with them that I designed. ”

And as for his propensity to play more than one string at a time, having started on guitar is a piece of the story, continued Lem. “Partly it is, but it’s also because I am the only back end for the guitar player. I always hated bands where when the guitar player stopped playing the riff and started playing the solo, the whole back end falls out. I always made sure there was plenty behind them. ”

Lemmy quickly became a beloved member of the Hawkwind clan. Appearing first on the band’s third studio album Doremi Fasol Latido (1972), plus Hall of the Mountain Grill (1974), Warrior on the Edge of Time (1975) and seminal 1973 double live album Space Ritual. Toward the end of his time with the band, Lemmy gave us signature rock songs soon to become Motörhead staples, namely “Lost Johnny” and “Motörhead. ”

“Lost Johnny” is a co-write between Lemmy and the Deviants’ Mick Farren, but “Motörhead” (existing in versions with Lemmy singing and with Dave Brock singing) is a rare sole-Kilmister credit and his last for Hawkwind before his firing. The set piece for the band and life philosophy to come would be written at the Hyatt House hotel on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles, ironic for the fact that Hollywood, and specifically the Strip, would become Lemmy’s home for the last decades of his life. “Did you know I wrote ‘Motörhead’ just down the street from here?” Lemmy told Jon Sutherland in 1982. “I was on the seventh floor of the Hyatt House, stoned out of my mind, playing Roy Wood’s guitar. Cars would keep stopping and cops would get out and get back in the car thinking, ‘I’m not going up there. ’”

Reflects Brock on that Warrior on the Edge of Time era, “That [album has] got the ‘Motörhead’ with Lemmy singing it, and me singing it. Basically, it’s the last record that Lemmy did with us, and after that, we changed quite a bit, because of Lemmy, or because Lemmy went. Lemmy was a great influence. ”

Lemmy’s firing from Hawkwind in May 1975 is the stuff of legends, almost amusing for the fact that he was already proving to be such an outlaw with substances that he could be fired from this notoriously drug-addled band for going too far.

“I was fired from Hawkwind,” explains Lemmy, in his curiously matter-of-fact manner indicative of the man’s view of an unjust world—in fact one in which he called his ex-mates fascists, rather than hippies. “I got busted going into Canada. My last gig with them was in Toronto. It was thrown out of court anyway, because it wasn’t what they said it was. So there was no criminal record attached to it. Hawkwind just threw me out because they were trying to throw me out for ages. ” The border agents thought the white substance was heroin, but it was speed, not yet banned.

Asked about how these stories take on lives of their own over the years, Lemmy agrees, adding, “You know, I tell you, it’s a funny thing. If you go back as long as I do, there are a lot of people in bands. Bands don’t remember that well apparently. Take any four members of Hawkwind and me, you will find five different recollections of the same incident and it runs all the way through your time with the band. You think, is that really what happened? Am I right and they fucked up? Hang on, what drugs were we doing that day? Was I out of it? Was there something that pissed me off? You try explain it and there is no explanation. You remember it different, because you’re standing in a different part of the room and somebody else spoke to you at the same time the incident went on. It’s funny. That’s why I really don’t rely on eyewitnesses anymore, man. If I was the cops, I’d throw that category out. ”

Concerning Lemmy’s ousting from the Hawkwind ranks, Nik Turner recalls that “the conditions in which he left were sad, really. We were playing in Detroit and were going to Toronto. We were in the United States still, and I think we stopped at a service station, and Lemmy went to the toilet and fell asleep in the toilet or something and we couldn’t find him. We were ready to go to travel on, and we looked everywhere for him. We couldn’t find him. We thought he’d probably hooked up with some people that he may have met and gone off with them, because he did spontaneous things like that, quite frequently. Not on a regular basis, but it wasn’t out of the question in our minds that he might’ve done that. And so consequently we traveled on without him. And apparently he did; he’d fallen asleep in the toilet. ”

Not so, says Lemmy, who has said that he wandered off with his camera to take some pictures and was knocked out and mugged of his camera, only to awaken and begin his odyssey.

“And then coming through customs,” continues Turner, “he’d been searched and they found what they thought was cocaine in his possession, and they arrested him for supposedly possession of cocaine. But when they analyzed it, they found out it was amphetamines, and they didn’t take such a dim view of amphetamines, so they let him go. But by this time, certain things had happened that had made him rather difficult to work with. And so we had a meeting and it was decided that he should leave the band. And then everybody was saying, ‘Well, who’s going to tell him?’ And nobody wanted to. But I just took the bull by the horns and said, ‘Well, I’ll tell him. ’ I had the very unpleasant job of breaking the news to him. And by this time we’d flown another bass player out from England. We had another guitarist, actually. We had Paul Rudolph from the Pink Fairies and he wasn’t a bass player either. He was a guitarist. But we knew he could play bass, and we asked him to come and play with us, and Lemmy was sort of sent back to Britain. I mean, it was all very sad, and Lemmy sort of held it against me, because I was the one who told him. Although now having explained it to him, it’s not something he still really holds against me. But it was all a bit of a problem, even though he did make it through the border. ”

Notes Hawkwind expert Rob Godwin, “Apparently they flew Paul Rudolph in from England because he was Canadian, and he could actually get into Canada without a work permit at the last minute. As for Lemmy’s bust, I’ve heard two stories on why he was let go. One was that he was released because they charged him with possession of the wrong thing, and under Canadian law you can’t charge somebody twice with the same crime. The other story was that they released him because amphetamine was considered a foodstuff in Canada and was not illegal. ”

To clarify, the band had played Detroit on a Saturday and traveled separately, stranding a temporarily lost Lemmy on the Sunday, as Nik explains, with most of the guys arriving in Toronto on that day. Lemmy, having had to hitchhike on the U. S. side and then having been flown from Windsor, Ontario, shows up on the Monday and the gig that night at Massey Hall is to be his last with Hawkwind. It is decided on Tuesday that Lemmy be sent home, and Paul Rudolph’s first gig with the band turns out to be Cleveland the following Friday, with an interim gig in Dayton, Ohio, having been canceled.

Further explaining the firing, Nik says, “Because we didn’t know where he was, and because we were told he’d been busted for hard drugs, it was very inconvenient. We didn’t know how long he was going to be in custody. We just had to make other arrangements, basically. So I think he played one gig and then we dispensed with him. And I mean, he was still on bail for supposed possession of hard drugs. It was all too complicated, really. It’s not the sort of thing you want in the band. All you want to do is get to the next gig and play. You’re on a tour, you’re committed, and you don’t really need those sorts of complications. You just want to get on with it and not deal with the side issues of people’s personal problems within the band. ”

“The story as it goes is that he was using different drugs to the rest of them,” says Godwin. “They were mostly into hallucinogenics—LSD and stuff like that—and pot, and he was taking speed. Him and Dik Mik, who was ostensibly the synthesizer player, they were speed freaks, and the problem—I don’t think was a personality clash as much as it was a case of that the speed guys would stay up for 24 hours and sleep for 24 hours, and frequently Lemmy would be late or barely show up to get in the bus or get on the truck or show up on stage. And the bust at the border was the straw that broke the camel’s back. If you look at the interviews he gave, he’s said he’d still be in the band if they hadn’t fired him. He loved being in that band. Dave loved playing with him. And that period of Hawkwind, if you actually listen to what they were playing when he was in the band, which is from January ’72 to May ’75, it’s the stuff that particularly stands out. ”

“He was not at all in the limelight,” answers Rob, when asked what Lemmy’s stage presence was like during his run with Hawkwind. “He was quite content to stand in the shadows as the rest of them were. They all stood in the shadows. In ’72, when I saw them, the house lights went down and all you can see onstage was red lights on the amps. And then Nik Turner walks out and starts throwing joss sticks into the audience—lit. You can imagine the fire marshal letting them do that now. And you cannot see the band at all. And then they start playing and the psychedelic lights and smoke take over and you never saw them. If you look at photos from that period, you will see that Lemmy is standing in the back lineup, along with Dave, and the only people who step forward to the microphone were Nik and Bob Calvert, when they were alternating doing narrations. And then Dave would step up to sing. But Lemmy was always singing backing vocals for the most part. And he’d stand in the back, right in front of his amps stacked up, virtually further back than the drummer—Simon King was further forward than Lemmy was. And Dave too. ”

“So Dave and Lemmy more or less stood side by side, back, almost behind the drummer,” continues Godwin. “And both of them said over the years that they had this telepathic sort of empathy when they were playing together. And Lemmy, right up to just before he died, said he’d never had that before or since with anybody else. Him and Dave were totally lockstep. You only have to listen to Space Ritual to hear it. It’s a live album, and you’re going, fucking hell, how are these guys doing this?!”

Cleaved from his space-rock soul brother, Lemmy managed to wrestle home from Canada three bass guitars and a suitcase on the plane. Licking his wounds in England, he would have to plot his next move, forever saddened by the loss of his Hawkwind family. His first plan of action back in London would be to abscond with what was on the band premises of his leftover Hawkwind gear and promptly paint it all black.

Table des matières

Introduction

Chapter 1 – “Hang on, what drugs were we doing that day?”

Chapter 2 – “A bullet belt in one hand and a leather jacket in the other. ”

Chapter 3 – Motörhead: “Like a fucking train going through your head. ”

Chapter 4 – Overkill: “He was a bit of a lad, old Jimmy. ”

Chapter 5 – Bomber: “They saw us as noisy, scary people. ”

Chapter 6 – Ace of Spades: “It wasn’t that it was the best we did; it was that it was the best they heard. ”

Chapter 7 – No Sleep ’til Hammersmith: “The bomber, the sweat, the noise—it was an event. ”

Chapter 8 – Iron Fist: “It was hard work getting Lemmy out of the pubs. ”

Chapter 9 – Eddie’s Last Meal: “A bottle of vodka on the table, a glass, and a little pile of white powder. ”

Chapter 10 – The Aftermath: “God bless him, little fella. ”

Selected Discography

Credits

Interviews with the Author

Additional Sources

Design and Photo Credits

About the Author

Martin Popoff – A Complete Bibliography

La description

Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers is the first book to celebrate the classic-era Motörhead lineup of Lemmy Kilmister, “Fast” Eddie Clarke, and Phil “Philthy Animal” Taylor. Through interviews with all of the principal troublemakers, Martin Popoff celebrates the formation of the band and the records that made them legends.

Reviews

“For 40 years Motörhead kicked your ass and made you deaf. They inspired an entire genre of music and the driving force was Lemmy. He was and always will be rock and roll. ” — Triple H, WWE Superstar

“Popoff's book was such an entertaining read . . . Martin Popoff and ECW Press have a must-read book for metal fans in Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers, whether or not the reader is a Motörhead fan. ” — LanceWrites blog

“The result is an entertaining and informative read that sheds no little light into the often-enigmatic Lemmy K. and his life's work, Motörhead, documenting the early years of one of rock music's most beloved and underrated outfits. The Rev highly recommends Beer Drinker and Hell Raisers for both hardcore Motörhead fans (duh) as well as anybody who lives and breathes rock ‘n’ roll. Grade: A+. ” — That Devil Music Blog

“There’s as much here for the fan to gobble up as a musician to enjoy, even someone who isn’t a Motörhead fan. ” — VintageRock

“Popoff maintains these 230 pages are like sitting in a bar with the guys. The text is keenly scripted as such. . . Good read. ” — Bravewords. com

“Popoff's book helps explain just how and why the band has been such an important and influential part of metal. ” – BiffBamPop. com

“As a musician and band guy, this is the kind of book I want to read about Motörhead. I mean, all the sex, drugs, and rock’n’ roll stuff is already legendary, as is the Live life on 10 attitude of Lemmy and the band. This book really captures what it was like to be in a band with these legendary idols. Even to this day, this book encompasses band-room banter that the inner circle of any gathering of musicians would truly appreciate and understand. ” — David Ellefson, Megadeth

“As is usually the case when it comes to books by Popoff, the wealth of research, details, anecdotes, and stories are impressive and simply begging to be devoured by all you ferocious readers out there. . . Whether you are a hardcore fan of the band or more of a casual fan of those filthy fucks, Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers is well-worth investing in and a great addition to the timeless Motörhead phenomenon. ” — Eternal Terror Webzine

“Popoff says that he is a huge fan of the band, something that comes through clearly in the book. ” — Decibel Magazine

“Popoff has managed to endearingly capture the history of that group . . . Popoff uncovers the true creative genius and ultimate demise of the lineup that recorded what are widely regarded as some of the most classic albums in hard rock history. ” — The Canton Repository

“A work of art that builds to a crescendo . . . Without a doubt, Beer Drinkers and Hell Raisers: The Rise of Motorhead is one of the greatest rock biographies ever. ” — TalkingMetal. com