They Called Me Number One

La description

Sellars tells of three generations of women who attended St. Joseph’s Mission in Williams Lake, BC, interweaving the personal histories of her grandmother and her mother with her own. She tells of hunger, forced labour, and physical beatings, and also of the demand for conformity in a culturally alien institution where children were confined and denigrated for failure to be white and Roman Catholic.

Récompenses

- Short-listed, Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize (B.C. Book Prizes) 2014

- Winner, George Ryga Award for Social Awareness in Literature (2014), Winner 2014

- Short-listed, Named one of 15 memoirs by Indigenous writers you need to read CBC Books 2017

- Short-listed, First Nation Communities READ‚ Periodical Marketers of Canada Aboriginal Literature award 2018

- Short-listed, First Nation Communities READ – Periodical Marketers of Canada Aboriginal Literature award 2018

- Short-listed, Burt Award for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Literature 2014

- Short-listed, 44 weeks on the B.C. Bestsellers list in 2013 & 2014! 2014

Reviews

As Canadians slowly begin to acknowledge the atrocities of the government-funded, church-operated Indian residential schools of the 19th and 20th centuries, Bev Sellars, Chief of the Xat’sull First Nation in Williams Lake, B.C., feels she has a mission “to make Aboriginal people realize that it is time [they] started living again and not just surviving.” Her memoir provides invaluable insight into the enduring effects of a tragic and shameful part of our collective past, and also helps to begin the process of healing.

They Called Me Number One describes the author’s experiences at St. Joseph’s Mission in the 1960s. Required by Canadian law to attend the residential school, Sellars and her siblings were removed from the care of their beloved maternal grandmother early in their lives: “No one asked our parents or grandparents if they wanted their children to attend the school. Gram always said to Mike, Bobby, and me, ‘I sure hate to send you kids back to the Mission but, if I don’t, they will put me in jail.’”

Sellars recounts numerous instances of severe physical, mental, and emotional abuse at the hands of the Mission’s staff and teachers, which resulted in long-term phobias, nightmares, migraine headaches, anxiety, alcoholism, and a disabling sense of inferiority. No aspect of Sellars’ troubled youth and early adulthood is off limits, including her responsibility for a devastating car accident that claimed her uncle’s life. More than once, she attempted suicide. Not just a jolting account of abuse, racism, and dysfunction, however, Sellars’ story is also one of healing and resurrection. She has abandoned an abusive relationship, earned two degrees, and become a community leader.

They Called Me Number One conveys anger at current and past governments, religious institutions, and a legal establishment that continue to condemn First Nations peoples to lives of fear and deprivation. Calling for the return of control over their resources, economies, and lives, Sellars declares her hopeful mission to help others “deprogram the destructive teachings of the residential schools” and take their rightful place in Canadian society.

The Cruelest School

In Canada, few subjects are as emotionally and politically charged as the former residential school system and the legacy it left behind. From the 1870s until the 1990s, more than 150,000 First Nations children were separated from their families and placed in government-funded, church-run schools, a policy that caused deep and lasting damage not only to people but also to an entire society.Much of what has been written about the residential schools system, however, is so densely academic or historical that many readers simply tune it out. But Bev Sellars’ memoir, They Called Me Number One, is neither, which is what makes it so accessible.

Torn from her family at the tender age of seven — as was required by law in the early 1960s — Sellars was enrolled at St. Joseph’s Mission School in Williams Lake, B.C., where she is now the chief of the Xat’sull First Nation. Although the school was just 40 kilometres away from her family home, “it might have been a million.” Sellars calls it her prison, and that’s hardly hyperbole. Her belongings were confiscated, she was given a number to replace her name and she performed manual labour.

Failure of any stripe was met with shaming and physical punishment — a leather strap on the palm of the hand, or a ruler rapped across the knuckles. Then there was the sexual abuse, which Sellars and some of her classmates endured at the hands of the clergy that ran the school.

Yet as harrowing as Sellars’ experience was, They Called Me Number One is not an especially depressing read. Her tales of life at St. Joseph’s can even be uplifting. She would steal glances at discarded newspapers for news of family members, and throw tea parties with her friends on Sunday afternoons. After being denied permission to use the restroom during prayer, a friend helped her conceal a pants-wetting accident from the nuns. It’s stories such as these that are a testament to the strength of spirit that people can summon in even the most trying circumstances.

There is already a wealth of writing that critiques the flaws in Canada’s historical and contemporary relationships with its Aboriginal Peoples (Sellars herself steers clear of drawing overtly political conclusions until the book’s final chapters), but the human stories of those who suffered have been harder to find. Sellars’ intensely personal memoir changes that.

"Sellars has given the readers an insight that we needed to hear." - Rabble.ca

"They Called Me Number One is from my perspective necessary reading across the generations. Over the past quarter century, I have been asked many times by students and others to recommend a book that speaks honestly and straightforwardly to the residential school experience in British Columbia and in Canada more generally. My long-time choice of Shirley Sterling’s My Name Is Seepeetza, written from the perspective of a child, now has a fine counterpart in Bev Sellars’s They Called Me Number One, crafted with the wisdom of hindsight." - Jean Barman

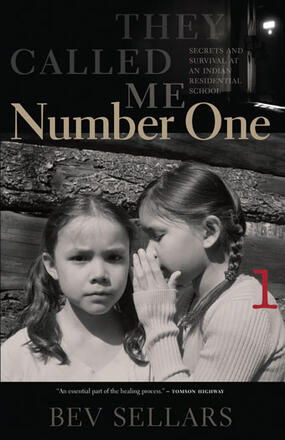

In this full-length memoir, Bev Sellars weaves her family history together with her experiences growing up in the interior of British Columbia in the 1950s and ’60s. Sellars recounts in an uninhibited voice some of the formative events of her youth: her twenty-month stay at the Coqualeetza Indian Hospital in Sardis and, centrally, her attendance of St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School near Williams Lake in the 1960s. Although a large portion of the memoir is focused on St. Joseph’s, a few chapters are devoted to telling the story of the author’s healing journey post-residential school: attending university, developing her political awareness, and becoming a leader in her own community. Throughout, Sellars succeeds at invoking a powerful sense of respect and admiration for her parents, grandparents, siblings, and relatives who have endured much pain in their lives as a result of the residential schools and official and unofficial racism. Her grandchildren grace the cover of the book, and it is to them and all those families who experienced the residential schools in Canada, the U.S., and Australia, who she dedicates her work.

Sellars’s memoir is a welcome addition to the expanding genre of published works that feature native peoples’ histories and testimonies of Indian Residential Schools. In recent years, works by Agnes Jack, Agnes Grant, Terry Glavin, and Celia Haig-Brown have sought to put native peoples’ experiences of residential schools front and centre in a broader effort toward political and economic justice in British Columbia and Canada. These works have complemented the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s mandate to promote understanding and reconciliation between native and non-native peoples through the gathering of testimony from residential school survivors.

Sellars’s memoir offers a unique contribution to this effort by showing how the inculcation of obedience to white authority in Residential Schools has hindered aboriginal peoples’ efforts to articulate their political grievances. She remembers vividly how students who disobeyed white authority figures at St. Joseph’s in the slightest of ways (such as sitting back on one’s heels when praying for long periods of time) were subject to cruel and excessive beatings. Students learned to be like “little robots” and developed a servile and passive attitude towards the schools’ white authority figures. Sellars reveals that for many years post-residential school, she could never contradict, correct or otherwise stand up to a white person, even in times when these actions would have been entirely appropriate. Sellars’s story is a testament to how the schools were a calculated attempt to politically pacify native peoples.

The memoir manages to weave these complex political themes into an emotional and highly personal narrative of suffering, pain, loss, and ultimately individual and communal overcoming. Sellars is a talented storyteller – in each chapter she skilfully layers on her recollections, gradually building toward a moment where she delivers a final memory or insight in a laconic and impactful fashion that seems to sum everything up perfectly. These emotionally charged moments in the narrative are arresting: the kind that make you fall out of the book momentarily in a need to digest, reflect, and feel the impact of what Sellars and her family have experienced. One chapter ends with Sellars recalling how after leaving residential school she was “scared of closed areas, and elevators especially freaked me out. I was scared of heights and being alone. Migraine headaches were a constant companion. I enjoyed the feeling of being hungry and at one point was very skinny, even borderline anorexic. In a nutshell, I was emotionally and socially crippled in my ability to deal with the world.” This honest and blunt delivery characterizes the entire memoir.

They Called Me Number One is an intimate, heartbreaking, and ultimately hopeful act of truth telling about residential schools in Canada. Aboriginal people who have attended the schools will identify with Sellars’s experiences and find inspiration in her ability to face the pain and suffering instilled in her rather than numb it. Non-aboriginal readers, if they open their hearts and minds, will be transformed by the life experiences and powerful narrative voice of Bev Sellars.

"They Called Me Number One is from my perspective necessary reading across the generations." - Jean Barman