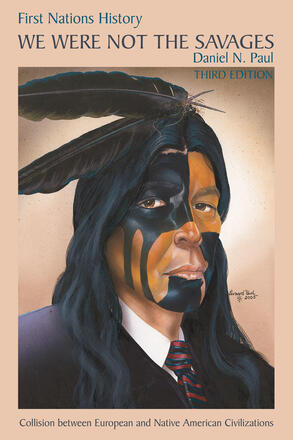

We Were Not The Savages, First Nations History, 3rd ed.

Collision between European and Native American Civilizations

La description

Reviews

Reviewed by Tasha Hubbard for Canadian Literature

Savage/Civilized has been a stubborn binary in the realm of Indigenous-European history, with the term ‘savage’ being exclusively applied to Indigenous peoples. Mi’kmaq author Daniel N. Paul builds a case that it was actually the European governments and settlers who deserved the “barbarian savage” mantle. He calls his bookWe Were Not the Savages “a history of one of the Native American peoples, a people who gave their all to defend home and country and fought courageously for survival.” As Indigenous peoples of Canada still find themselves locked in this struggle, a well-researched revisionist history of contact between the Mi’kmaq and Europeans is of particular value as it turns the savage/civilized binary on its head.

We Were Not the Savages was first published in 1993. In this 3rd edition, Paul retains most of the material of the 2nd, including extensive quotations from primary sources outlining the trajectory of European contact, colonization, and twentieth century racism and centralization as well as the impact of this trajectory on the Mi’kmaq people. The book contains detailed descriptions of early Mi’kmaq civilizations, European contact and conflict, and the treaty-making (and breaking) process. In the updated edition, Paul adds contemporary developments, including more details of the infamous Scalp Proclamations, a particularly disturbing aspect of Indigenous-European relations. Several of these proclamations were issued by colonial governments in the mid 18th Century. One, issued by Governor Charles Lawrence, remains on the books of Nova Scotia’s laws, and Paul outlines the twenty-first century attempt and failure to have it struck from the records.

A long-time employee of the Department of Indian Affair as District Superintendent of Reserves and Trusts for Nova Soctia, Paul includes stories of racism and oppression from his own experience to supplement his account of the more contemporary struggles for Mi’kmaq people. He is not afraid to stray from the typical ‘objective’ tone found in most historical texts. This edition includes an ‘Afterword’ which provides some textual history of We Were Not the Savages, and the reception to its difficult and controversial message. Paul is an author heavily invested in his past and his people, and he is telling a history that many would like to forget.

In Weasel Tail, the emphasis is on ‘not forgetting’ the knowledge and stories of this particular ‘Old Man’. Following in the vein of such texts as Write it on Your Heart, a collaborative effort of Okanagan storyteller Harry Robinson and editor Wendy Wickwire, Weasel Tail is also a collaboration between storyteller and historian.. Audio recordings of Joe Crowshoe that began in the 1990’s by Brian Noble were halted and then taken up again by Michael Ross. The resulting 20 hours of Crowshoe’s stories were translated from Blackfoot to English, left uncondensed, and kept closely to the stories’ original form. The process is described by Ross as “piecing together a complicated jigsaw puzzle.” Regardless of the challenges, the final text is a wealth of personal history and Blackfoot cultural knowledge. It provides an example of a life lived in a good way. Unfortunately, because Crowshoe died in 1999, he was unable to participate in the actual editing process. Still, his wish for his stories to be disseminated has come to fruition.

Ross surrounds Crowshoe’s stories with photos, notes, and sidebars in order to provide “insight into the subjects he talks about.” The notes and sidebars provide quotations from other historical texts; short biographical sketches of photographers, anthropologists and Blackfoot elders; and contextual information on Blackfoot culture. This allows the book to be read in multiple ways: a reader familiar with the Blackfoot history and culture could choose to focus on the stories themselves, or a reader less knowledgeable can stop to read the assorted marginalia alongside the stories, in order to understand the “historical context of culture, time, and place.” The stories tell of specific ceremonial traditions, trips Crowshoe took abroad, and family histories. Several of the stories read as conversations between Crowshoe, his wife Josephine, and his sons Reg and Ross. Together Joe and Josephine held several important ceremonial positions within Blackfoot society. Ross notes how she would interject “Listen to this!” at particularly important junctures in the stories. The subtext of her comment is echoed by Indigenous leaders and scholars, who tell us that stories are inherently necessary for community’s survival. We should all listen.

Whether stories are of historical events or of a more personal nature, all are valuable. We are told that both the oral and the written have roles to play in understanding our pasts in order to negotiate our futures. Both of these books participate in this multi-layered approach of telling Indigenous history.