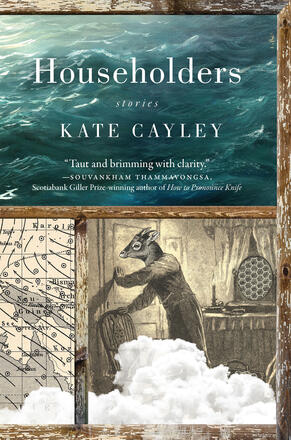

Householders

La description

Linked short stories about families, nascent queers, and self-deluded utopians explore the moral ordinary strangeness in their characters’ overlapping lives. Householders moves effortlessly from the commonplace to the fantastic, from west-end Toronto to a trailer in the middle of nowhere, from a university campus to a state-of-the-art underground bunker; from a commune in the woods to a city and back again, with the precision and clarity of short stories, but the depth of a novel.

Reviews

Praise for Householders

“A book that so assiduously interrogates notions of identity and belonging ... Cayley’s language is precise and evocative ... Each of the collection’s stories—from ‘Pilgrims,’ about a woman who impersonates a nun online to find sympathy for her difficult domestic situation, to the stunning opener, ‘The Crooked Man’—contains writing that impresses with its barbed acidity as much as its clear-eyed observation ... The lambent prose frequently belies the emotional heft of the stories, which creep up on a reader.”—Quill & Quire, starred review

"I devoured this book. I hoovered it; I let its sorrow, its wonder, its yearning, swirl in the vacuum bag of my chest cavity. On every page there is so much honesty, insight, so much complex understanding."—Anne Fleming, Xtra Magazine

"Kate Cayley showcases virtuosic writing and captivating settings alongside intriguing plots that are handled with marked assurance from beginning to end ... More than reflecting sheer invention or technical mastery, the stories are anchored by multi-faceted characters reacting to or navigating unique practical and ethical dilemmas, which Cayley investigates with a thoughtful thoroughness."—Plenitude

"What Cayley has a gift for is getting into the minds and, more importantly, the hearts of characters far from the usual and revealing their humanity with a gentle incisiveness."—Maple Tree Literary Supplement

“It would be something of a shame to read any of these stories individually, or to read them just once through, as moving outside and around them is one of the pleasures of this text. Householders is not a collection about the singular self, but about the individual uneasily negotiating subjectivity in a manner that is intrinsically relational; and appropriately, the narratives seem to continue into and across one another, propelled by differences that underscore their symmetries."—Full-Stop Magazine

"Cayley writes with a passion that seems to extend that longed-for forgiveness to her characters when they cannot bring themselves to do it for themselves."—Memphis Flyer

“The stories in Householders are haunting and enigmatic, with a clarity of emotion that cuts through the dreamlike atmosphere Cayley has crafted ... With incredible attention to the nuance of interpersonal relationships—whether familial, romantic, situational, dysfunctional—each story in Householders is a window into an eerie but wonderful world.”—Fawn Parker, 49th Shelf

“You don’t have to come from a foreign country to be a stranger in your land. Cayley’s haunting short stories weave together stealthily, gentle until the cosh strikes your skull … Brutally, beautifully lyrical.”—Lavender Magazine

“Full of startling turns of phrase and evocative descriptions ... Cayley’s background as a poet—she has published two collections of poetry—shines ... With Householders, Cayley has envisioned a world that mirrors our own like a distorted funhouse—a place where the moral and physical stakes are heightened, where emotional bonds run deeply, and where something menacing is often lurking. It’s a frightening world, but it makes for a compelling story collection, as good to tear through for the narrative as it is to savor (and savor again) for the language.”—ZYZZYVA

“Literally took my breath away … Kate Cayley is splendid in her deft arrangement of the sentence, and in her depiction of the quotidian but just askew enough to be new and surprising. These stories are rich, absorbing, and oh so satisfying, and I predict this as one of the big books of the fall literary season.”—Kerry Clare, Pickle Me This

"Cayley’s ability to create characters that fascinate is something to behold."—Anne Logan, I've Read This

"Reading each story in Kate Cayley’s Householders is like entering a household, one that is unique in its treasured secrets and hidden corners of glory and shame. The inhabitants—a trio of aging hippies, a blogger masquerading as a nun, a group of traumatized escapees from a fanatical commune, a washed-up but still brilliant musician—are all seekers after whatever good life, or good death, they can find. Having met them, the reader is left with a lingering sense of responsibility, as for worrisome old friends who are loved in spite of themselves."—KD Miller, Scotiabank Giller Prize-nominated author of Late Breaking

"Taut and brimming with clarity."—Souvankham Thammavongsa, Scotiabank Giller Prize-winning author of How to Pronounce Knife

"Cayley’s world is a dangerous place, all the structures built with discarded slivering wood and rusted nails, but one where strange sacredness arrives in the middle of the ordinary day. The mysterious reasons that push her misplaced, displaced people are as convincing as memories, painful but necessary to relive. Read these stories, you’ll be glad you did."—Marina Endicott, author of The Difference

Praise for Kate Cayley

"Cayley illustrates our human desire for permanence, and the corresponding impermanence of the physical body. Other Houses weaves a rare complexity of contemplations through metaphor, shape-shifting, and philosophical considerations. Efficiently stated, Cayley’s ideas are wise and well worth a read."—Quill & Quire

"Though its narrative is simple, the play is eloquent, subtly shaped and offers a formidable confrontation between its two characters, a painter and an army officer."—NOW Magazine

"When This World Comes to an End marks a captivating poetic debut for the busy writer ... Despite its breadth of history, When This World Comes to an End offers a succinct reflection of what has been and what will be. The purview of history is considered through known figures just as much as the insignificant acts of the everyday."—Toronto Review of Books

"Cayley shows us, in How You Were Born, that the impulse to collect and then work through anxiety imaginatively is important and powerful."—Cleaver Magazine

"Reading each story in Kate Cayley’s Householders is like entering a household, one that is unique in its treasured secrets and hidden corners of glory and shame. The inhabitants—a trio of aging hippies, a blogger masquerading as a nun, a group of traumatized escapees from a fanatical commune, a washed-up but still brilliant musician—are all seekers after whatever good life, or good death, they can find. Having met them, the reader is left with a lingering sense of responsibility, as for worrisome old friends who are loved in spite of themselves."—K.D. Miller, Giller-nominated author of Late Breaking