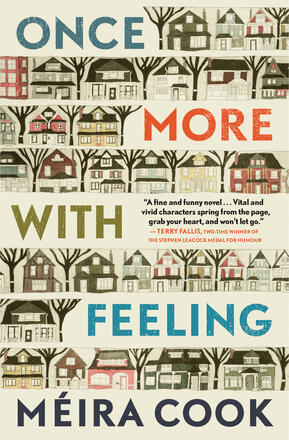

Once More with Feeling

La description

In the tradition of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Olive Kitteridge comes Once More with Feeling, an exquisitely crafted, beautifully written, and wholly delightful novel about the place we call home and the people we call our community, told through intersecting moments and interconnected lives.

Récompenses

- Short-listed, The Margaret Laurence Award for Fiction 2017

- Winner, Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award 2017

- Short-listed, McNally Robinson Book of the Year Award 2017

Reviews

Meira Cook . . . writes prose so fluid, so effortless, so vivid, you’re swept away on its sheer beauty and power. . . . Once More With Feeling manages to be both sharp and tender, tragic and fiercely funny, and wholly satisfying.

- Toronto Star