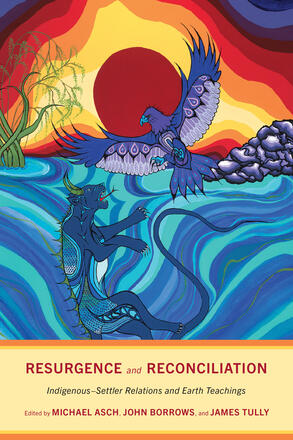

Resurgence and Reconciliation

Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings

La description

The two major schools of thought in Indigenous-Settler relations on the ground, in the courts, in public policy, and in research are resurgence and reconciliation. Resurgence refers to practices of Indigenous self-determination and cultural renewal whereas reconciliation refers to practices of reconciliation between Indigenous and Settler nations, such as nation-with-nation treaty negotiations. Reconciliation also refers to the sustainable reconciliation of both Indigenous and Settler peoples with the living earth as the grounds for both resurgence and Indigenous-Settler reconciliation.

Critically and constructively analyzing these two schools from a wide variety of perspectives and lived experiences, this volume connects both discourses to the ecosystem dynamics that animate the living earth. Resurgence and Reconciliation is multi-disciplinary, blending law, political science, political economy, women’s studies, ecology, history, anthropology, sustainability, and climate change. Its dialogic approach strives to put these fields in conversation and draw out the connections and tensions between them.

By using “earth-teachings” to inform social practices, the editors and contributors offer a rich, innovative, and holistic way forward in response to the world’s most profound natural and social challenges. This timely volume shows how the complexities and interconnections of resurgence and reconciliation and the living earth are often overlooked in contemporary discourse and debate.

Reviews

"Resurgence and Reconciliation: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Earth Teachings makes a sustained contribution to ongoing reconciliatory efforts through the exemplary work of Indigenous and non-Indigenous scholars alike."

- Tyson Stewart, Nipissing University